While the question of the artistic value of video games has always been a pointless and self-indulgent one, it’s hard to deny the impact of that ongoing debate on game productions from all levels of the industry. From the smallest independent creations to the most sprawling corporate behemoths, we see the same apparent insecurity, the same desperation to be taken seriously. To consider these works on these terms isn’t just boring, it’s a critical submission to marketing. It is far more interesting to consider why those terms are what they are. What does the game designer (and, more significantly, marketer) consider a baseline for artistic worth?

For some reason, the answer is always cinema. Games, particularly on the AAA scale, have for decades used film as both inspiration and barometer. “It’s like playing an interactive movie” has been both text and subtext in the critical response to countless games. It’s certainly easier to draw parallels between the general characteristics of a AAA video game and a film than between a game and a novel, which has no visual or sound design, or a painting, which has no movement in its imagery, or a song, which can be heard but not seen. These are all rather basic understandings of these mediums, but you see the point: Games are more like films than they are like anything else.

What’s worth remembering, though, is that this similarity was a choice rather than an inherent feature. Games used to be far more distinct from films in their aesthetic qualities and methods of engagement. Pac-Man and Galaga bear about as much similarity to books or paintings or music as they do to films. Even many games at the advent of 3D were structurally alien; you could not imagine someone editing clips of Super Mario 64 into anything resembling cinematic narrative, and games like Resident Evil and Silent Hill were more obviously influenced by films but still featured novel visual approaches far more indebted to the demands of their own medium.

There were, of course, plenty of alternate examples. RPGs have pretty much always featured more recognizable narrative building blocks. Games based around full-motion video cutscenes like Phantasmagoria incorporated literal filmed elements into a point-and-click adventure game structure. Still, these works feel more like synthesis than imitation, and their typically low production values meant that they were typically classified as campy cult objects more than anything else. Still, by the late 1990s, the swing towards movies was in full effect. After a while, games became far more interested in resembling films than they were in engaging with the properties of their own medium. Finally, in 2020, we arrive at Ghost of Tsushima. This is the year we entered Kurosawa Mode.

Ghost of Tsushima is, on the surface, essentially identical to any other Sony AAA open world game from the past several years. The game’s protagonist, Jin Sakai, wanders around a massive map, runs into random enemy patrols, picks up side-quests to help random villagers, follows objective markers to locations, stealthily infiltrates an enemy camp and quietly takes out guards until he is discovered, presses a button on a glowing plant and collects 2x bamboo to be used in crafting equipment upgrades. It’s all quite familiar.

How does a game like this distinguish itself? The better question is, why would it want to? Games like this, which can be played in a lazy, relaxed state, serve their purpose well. I’ve played tons of them purely as objects to occupy my hands while I zone out and listen to podcasts. Ghost of Tsushima is far from the best example of this subgenre; its controls are a hair too clunky and thus require a bit too much attention. Combat, too, centers on timing that is slightly less forgiving than it could be. Ghost of Tsushima wants you to pay attention to it, despite possessing nothing of substance to earn that attention. You can almost see the gears turning in the heads of the designers at this point, like Skinner plotting to disguise fast food as his own cooking. What if there was a way to dress up this bog-standard open-world action game as something more, something with deep roots in the history of another medium? What if there was a Kurosawa Mode?

What is Kurosawa Mode? It’s essentially a Snapchat filter over the entire game. The images become greyscale and covered in fake film grain and scratches (even in the menus), the sound gets a little fuzzier, and a few elements are removed from the game’s HUD for the sake of “immersion.” In theory, the mode is supposed to make you feel like you’re playing an Akira Kurosawa film. In practice, it’s illustrative of the ways in which games betray their misunderstanding of cinema in their attempts to imitate it. I played through Ghost of Tsushima in Kurosawa Mode for around 15 hours, and the game felt far more compromised than enhanced.

This entire piece is, I acknowledge, written at the risk of taking a marketing gimmick far too seriously. As I shared my progress through the game, I frequently saw people responding with mock frustration that I was playing the game wrong. Ghost of Tsushima isn’t supposed to be played in Kurosawa Mode all the way through, they told me. If that’s the case, and I believe it to be so, then why does the game prompt the player to turn it on before they even start playing? Is the player supposed to go into the display settings to toggle it on and off as they play? I know it’s not just meant for the game’s photo mode, because you actually can’t change it from that menu. What is the point of Kurosawa Mode if not to play it? And once you are playing it, how can you possibly stand to continue doing so?

It’s important to note that the game’s visuals are, in their unaltered state, occasionally quite nice to look at. At one point early on, I entered an area called Golden Forest. I saw grey trees and grey leaves on grey dirt and grey grass. I turned off Kurosawa Mode to see what the area really looked like, and was instantly struck by the vibrancy of the colors. I ended up doing this several times throughout the game, and each time was the same. Far from the black-and-white compositions of the actual Kurosawa, the mode that bears his name is nothing but indistinguishable splotches of grey. Why does a mode named after one of cinema’s greatest visual stylists look so utterly disgusting?

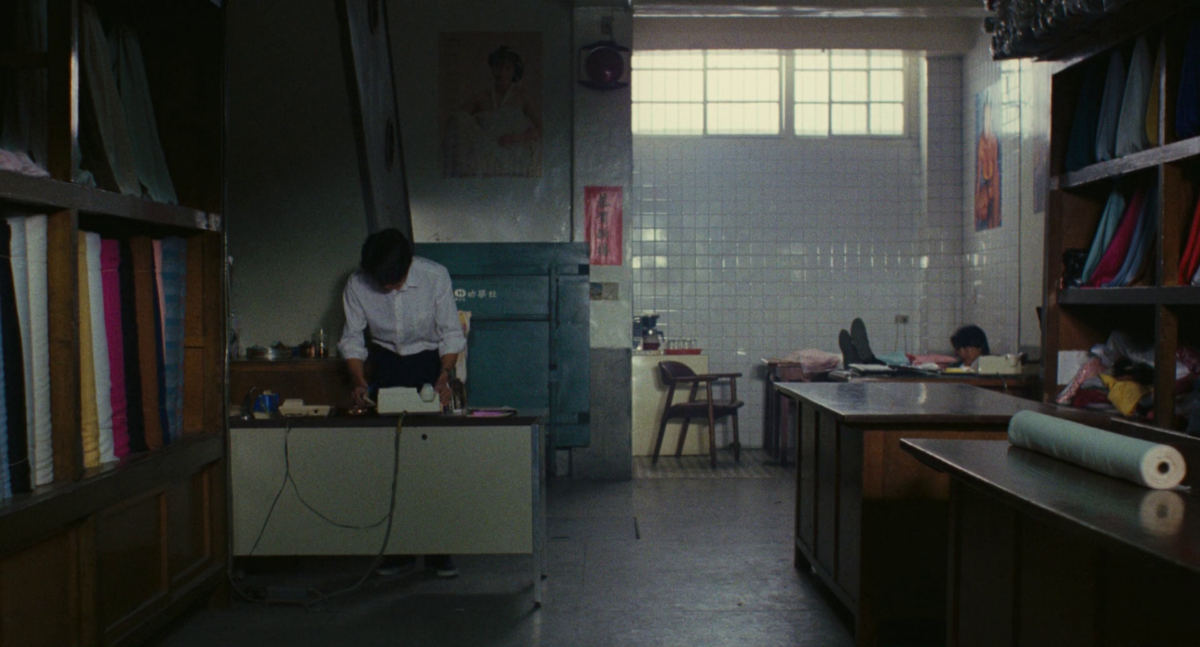

The answer is obvious, though I hesitate to put too fine a point on it. The designers of Ghost of Tsushima have no understanding of cinema as a visual art form, only as a container for reference points. If you put a shot from Kurosawa Mode next to a shot from a Kurosawa film, you may see superficial similarities. There might be a samurai in both, for example. Yet Kurosawa was a visual stylist with few equals in his medium’s history, and Sucker Punch Productions, to be as kind as possible, are not. The images in Kurosawa’s black-and-white films are full of staggering depth and complexity and texture, perfecting and then reinventing common techniques. The images in Ghost of Tsushima couldn’t be reasonably expected to scratch his mastery. But they don’t even seem to want to try. The game stays true to the stiff shot/reverse compositions and rhythms of countless other AAA titles, as though it can think of nothing more interesting to do in a cutscene than sit still and listen to people talk.

Certain scenes weakly gesture at a sort of One Perfect Shot-ish conception of cinematography. There’s a lot of symmetrical compositions of two warriors squaring off with a picturesque landscape behind them. A sunset, a sprawling field, a fortress. It’s imagery for desktop wallpapers more than anything else, an artistic impulse towards Twitter screencap threads.

Most of the time, though, Kurosawa Mode delivers a muddled, inscrutable mess. During the opening setpiece, a chaotic battle on a beach, the screen is filled with smears of grey which render the action difficult to read. Kurosawa himself never ran into this problem. An iconic action scene in Seven Samurai takes place in a ferocious downpour, yet the actors and objects on screen are always clear and distinct. I’ll give Sucker Punch the benefit of the doubt that the technologies used in game production are at least partially to blame for this problem. I don’t know enough about those tools or the process of using them to feel comfortable entirely blaming the artists.

That being said, the problem is right there on screen, and it never goes away. These images have no character or texture or life. Kurosawa Mode makes Ghost of Tsushima a constant stream of blotchy, indistinguishable grey. The fake film grain effect applied on top feels like a bandaid on a severed limb. Does Sucker Punch know what film grain is? Like so many things in this game and this mode, it seems to be present only as a contextless point of reference. They care more about triggering shallow memories of old movies than actually learning anything from them which they could put into practice.

Sometimes this even directly affects the experience of playing the game. Early on, I was given a quest to track down something or other which required following a hand-drawn map. I was told to look for patches of purple flowers to lead me in the right direction. You can imagine the conundrum here.

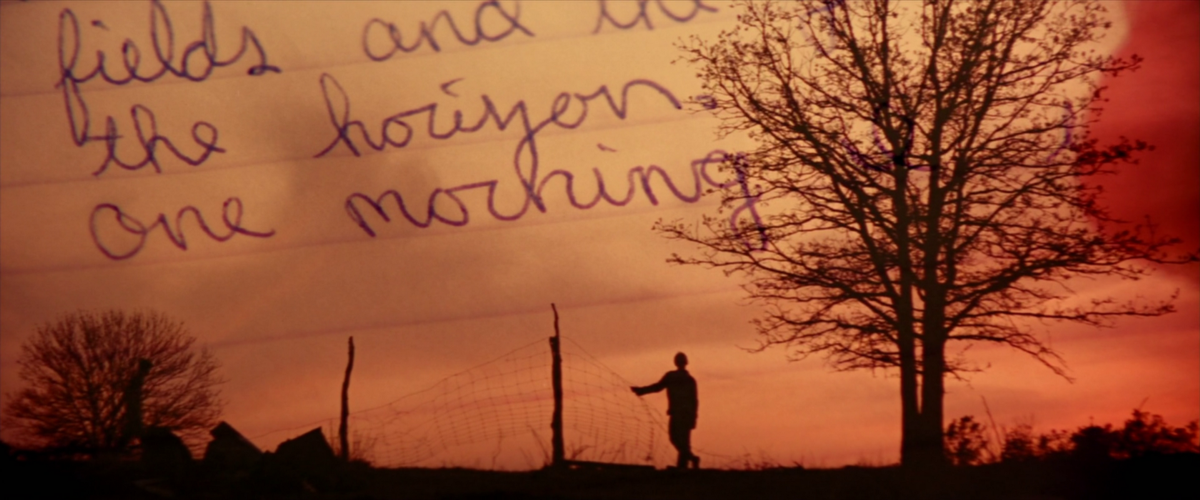

How would the real Kurosawa have solved this issue? In his film High and Low, shot in black-and-white, the appearance of pink smoke represents a key development in the story. Kurosawa illustrates this by, well, literally illustrating it: the smoke is colored pink amidst the otherwise entirely grey city backdrop. Kurosawa wasn’t precious about leaving the black-and-white cinematography undisturbed, as though doing so preserved some kind of ethereal artistic experience. On the contrary, the film is all the better for this one striking break in form.

All this is to say that Sucker Punch not only could have just made the flowers in question appear purple despite the Kurosawa Mode filter, but doing so would have actually been a direct reference to the man the mode claims to be inspired by. Perhaps the developers had never seen High and Low, or perhaps they just didn’t bother to consider the issue that Kurosawa Mode would introduce for this quest. Whatever the case, I spent what felt like ages stumbling around in the general vicinity of the objective trying to deduce which flowers were meant to be the purple ones, thinking that surely the developers must have added in a way to tell the difference even without being able to see the colors. Eventually, out of frustration, I turned the mode off in order to complete the quest. The flowers were right in front of me the whole time. This isn’t the only quest in the game which relies on the player noticing colors in the environment. In fact, a key mechanic which lets the player know which incoming attacks can be parried and which cannot relies on flashes of red and blue which Kurosawa Mode renders completely indistinct.

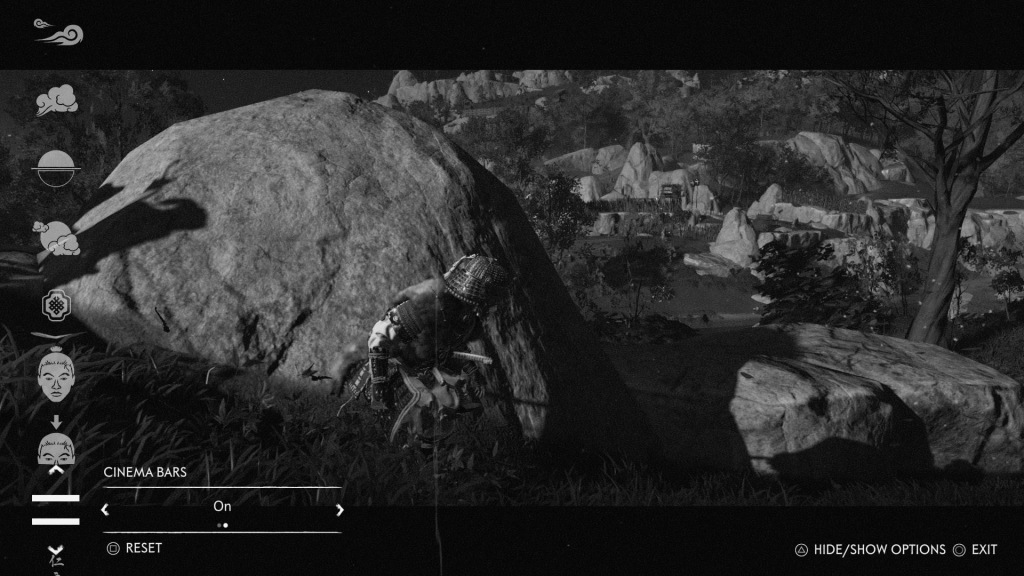

Even without color being a factor, though, the smudgy visuals of Ghost of Tsushima frequently make it a nightmare to play. In the next screencap, for example, see if you can tell where the enemies are, and how many of them are present.

Having trouble? So did I during this section. I died again and again because I could not for the life of me tell what was going on. Since the game required me to kill every enemy in the area to progress, I ended up sprinting around aimlessly hoping to run into someone I could kill. A 3D game should prioritize the player’s ability to orient themselves in its space. Perception of distance, shape, speed, and the player character’s movement capabilities should be attained intuitively. Games had this figured out almost from the moment that 3D movement was introduced. The gameplay in Super Mario 64 may feel a little sluggish in 2020, but knowing where you are and what’s around you isn’t an issue. The degree to which Kurosawa Mode annihilates an aspect of its medium which was figured out decades ago is genuinely staggering.

Putting the gameplay interactions aside, though, I think Kurosawa Mode does a good job of demonstrating how Sucker Punch’s pretensions of cinematic inspiration reveal a gaping lack of knowledge about the medium. One of the more amusing instances of this is during cutscenes, where black bars appear on the top and bottom of the screen to imitate a widescreen aspect ratio. (Worth mentioning that several of Kurosawa’s samurai films, including Seven Samurai and Rashomon, were not shot in widescreen ratios.) Hysterically, when this happens, the fake film grain and scratches of Kurosawa mode actually appear on top of the black bars as well. Anyone who knows even a little bit about film can tell you that (unless you’re watching a hard masked print, I suppose) this isn’t how movies work. No one told Sucker Punch, apparently. No one even seems to have told them what that masking effect even represents. In the game’s photo mode, it refers to the effect as “Cinema Bars.” Cinema bars.

It’s always at best amusing and at worst annoying when games try so hard to be like movies. Ghost of Tsushima represents a new low in failed ambition for the medium. It would be one thing for Kurosawa Mode to just be what it is: a lazy, hastily assembled marketing stunt for an otherwise generic AAA action game. It’s something more than that, though. It’s a perfect representation of how the game industry’s supposed cinematic ambitions come at the expense of innovation in their own medium, and sometimes even at the expense of making their work playable at all. It’s unlikely that this is going to change any time soon. These studios aren’t just going to get over their obsession with chasing cinematic signifiers. If Ghost of Tsushima showed anything, it’s that this stuff sells. The only hope I have is that maybe, when the next game like this rolls around, the producers will have watched a few more of the movies they claim to be inspired by. They might even enjoy them.